Welcome to the Rudloe and environs website.

Here you will find news, articles and photos of an area that straddles the Cotswold Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in north-west Wiltshire.

Contributions in the form of articles or photos are welcome. Even those with completely contrary views to mine!

Thanks to the website builder 1&1 and Rob Brown for the original idea.

Rudloescene now, in January 2014, has a sister, academic rather than anarchic, website about Box history here: http://www.boxpeopleandplaces.co.uk/

It contains thoroughly professional, well-researched articles about Box and its people.

Contact rudloescene through the 'Contact' page.

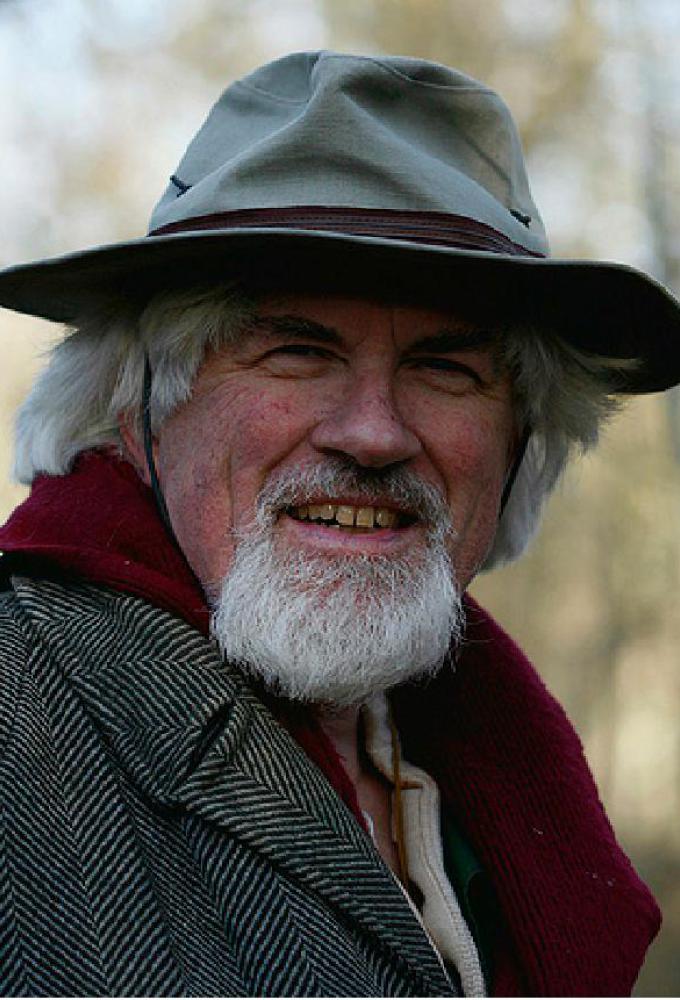

Much of the content of rudloescene was inspired by Oliver Rackham, botanist, who died on 12th February 2015

Oliver Rackham's obituary, below, was taken from The Times of 7th March 2015. I hadn't realised that he was brought up in Bungay, Suffolk which is the realm of a good part of the paternal side of my family. My aunt (my father's sister-in-law) and her family live in this neck of the woods and my father was brought up by his maternal grandmother in Wissett.

I have treasured his books for many years. These include: Trees & Woodland in the British Landscape (1976), The History of the Countryside (1986), Woodlands (2006) and The Ash Tree (2014). As the obituary says, the last was written from memory from his hospital bed in 2014.

As he bicycled through Cambridge in brightly coloured socks and sandals, even with a dinner jacket, white hair and beard streaming, one could see why Oliver Rackham had been called the “High Druid” of ecologists. Yet while the tag fitted his donnishly eccentric appearance, it also denoted his standing in a field of study that he revolutionised.

His career was largely devoted to revising long-held notions about how the British landscape, and in particular its woodlands, had come to be shaped. Unusually for an academic, he was also a gifted communicator. His ideas soon gained influence in official circles and were popularised through his wryly well-written books, notably The History of the Countryside (1986). Among those who listed his books as favourite reading was the Duchess of Devonshire, the châtelaine of Chatsworth.

Chief among Rackham’s discoveries was that all forms of land benefit from management by man in order to retain their “natural” diversity. Whereas the postwar fashion had been to abandon traditional practices such as coppicing, in which trees are cut back regularly to their roots to promote new growth, Rackham showed that the method allowed more light to reach the forest floor and promoted a variety of animal, insect and vegetative life.

Other misconceptions that he dispelled included the belief that the demands of the iron industry had devastated Britain’s woods, and that the building of the Tudor navy had felled the oak forests. By studying medieval timber-framed barns, Rackham was able to show that suitable wood for ships had been in short supply as early as the Middle Ages.

He warned against new threats to the landscape, including unwanted immigrants in the form of non-native trees, imported on an industrial scale from other parts of the world with soil containing pests and diseases that faced little resistance in Britain. His last book, The Ash Tree (2014), written from memory while he was unexpectedly in hospital, was prompted by the spread of chalara or ash dieback.

Rackham also inveighed against the huge rise in the muntjac deer population. At a dinner in 2006 to celebrate his appointment as an honorary professor of historical ecology at Cambridge, the main course was venison.

The only child of a bank clerk and his wife, Oliver Rackham was born in 1939. He spent his early years in Bungay, Suffolk, and was then educated in Norwich, winning a scholarship to Corpus Christi, Cambridge. He intended to become a physicist but became enthralled with botany. After taking a first in natural sciences, he began to look at how the rates of photosynthesis varied in plants and was appointed a Fellow of Corpus in 1964.

By the 1970s he was absorbed by the challenge of unravelling the warp and weft of the countryside’s past. His first book, in 1975, a study of Hayley Wood in Cambridgeshire, focused like much of his work on the silviculture of the eastern counties where he had grown up. Having learnt Latin to read the 13th-century records of Ely Cathedral’s Coucher Book — he liked to call trees by their medieval name of “pry” — he was able to show that the wood was largely unchanged in the intervening 700 years. This came as a revelation, as did Rackham’s conclusion that pannage — the use of pigs to eat up acorns which may poison cattle — was less common than thought, as was the damage done by rooting hogs to woodland. His conviction that the countryside was more robust than believed became an abiding theme of his work.

In the 30 years after the war, some 40 per cent of ancient woods had been planted (for profit) with conifers instead of with native trees. He once lamented: “Much of England in 1945 would have been instantly recognisable to Sir Thomas More and some areas would have been recognised by the Emperor Claudius.” He argued that conservation decisions should be for government not for individual landowners, and from 1985 the Forestry Commission adopted a new policy of restoring native woodland.

Rackham, who never married and had no children, was never afraid to speak his mind. Field trips with him were regarded as a highlight by his students at Cambridge — though great leaps were often needed to keep up with him. Rackham had a habit of striding off abruptly as some hedgerow or pollard caught his interest.

Similarly, his audience would be jerked from their line of thought by the reminder that the Norfolk Broads are man-made or that the Great Storm of 1987 had been a boon in undoing much unwanted planting. He also liked to point out that a hollow tree is still in its normal life-cycle instead of decaying.

Rackham took pride in the fact that England has a tradition of maintaining its ancient trees, unlike much of Europe. Yet the Mediterranean landscape, especially that of Crete, which he first visited as the botanist to an archaeological expedition in 1968, also fascinated him.

Rackham was appointed a Fellow of the British Academy in 2002. As Corpus’s longest-serving Fellow, he was invited to become its master for a year in 2007 while a new one had unexpectedly to be sought. One friend noted how “papers seemed to occupy the floor of his office, whilst his sandals held pride of place on the desk!”

Oliver Rackham, OBE, ecologist and botanist, was born on October 17, 1939. He died on February 12, 2015, aged 75